In attempting to visualize the state of warfare on the grand scale, we generally use maps, and thus symbolic markers along these maps, in signifying troop movements, front lines, etc. The symbols used in our visualizations have changed in accordance with the difference in grand strategies of the times. In wars prior to the conventional concept of front line warfare, which came to full fruition with the first World War, the military situation is best shown not with front line control, but with troop movement and fort control.

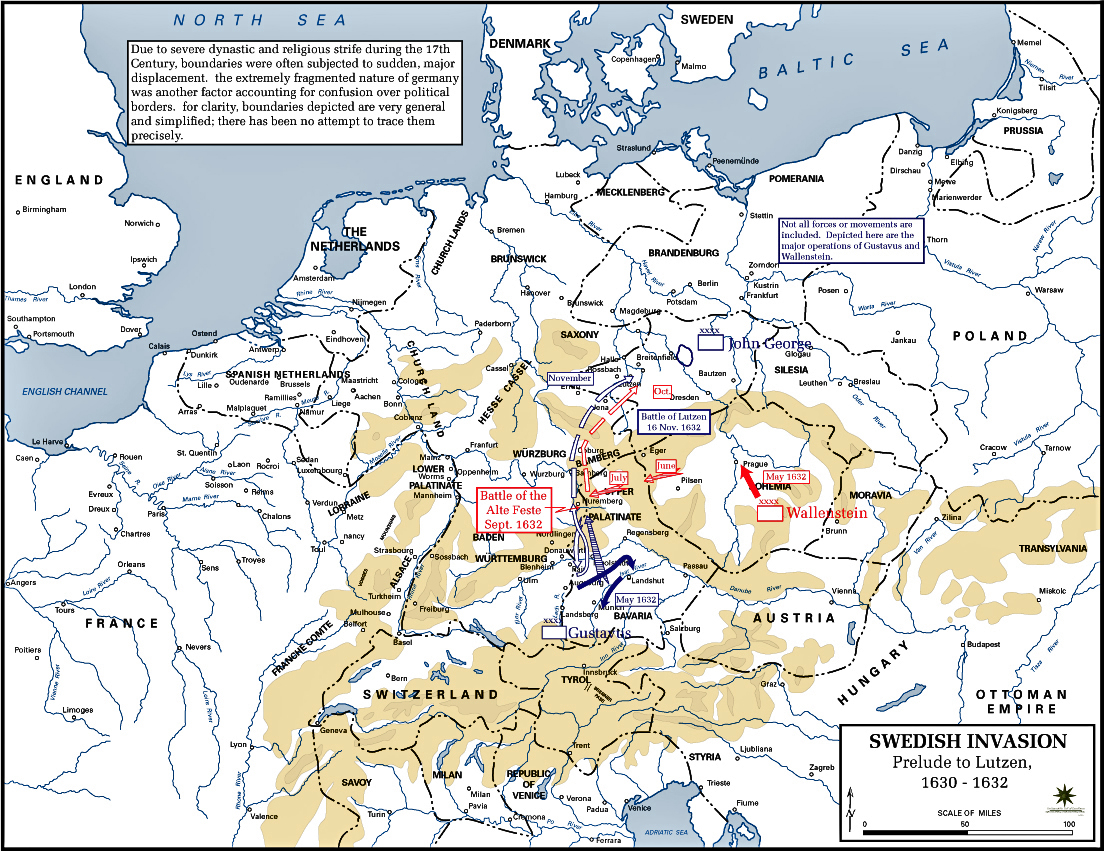

Here we see a map of the campaign of the Thirty Years War, specifically of the initial stages of the Swedish intervention under Gustavus. Note that troops seem to move without regard to borders of warring nations, with Wallenstein’s army moving deep into Saxony after the defeat of Gustavus’s army in the Battle of Alte Veste.

Furthermore, we also can observe the English campaign in the initial stages of the Lancastrian War, as a part of the Hundred Years War. As the English army moved through the region of Normandy, the French army shadowed, and aside from harassment from the French advance guard, did not directly engage the English forces until the famous battle at Agincourt. As we can see in this campaign, as well as our example in the Thirty Years War, the concept of a front line is completely alien, and thus warfare on the grand strategy level can be conceptualized as analogous the movement of dots along a map, the dots representing a cohesive and concentrated military force.

The reality for the states before the rise of industrialization and the advent of conscription was that complete and continuous control of the peasantry was not necessarily important, as the state’s main interaction with the peasantry was in terms of tax collection. What mattered for military might at those times was a strong aristocracy and money for mercenaries, not control of industrial and population centers. This, of course, began to change towards the end of the modern era. Industrialization and mechanization naturally led to the usage of advanced and expensive technologies in warfare, which required significant capital investment in the form of factories and industrial capacity. Furthermore, conscription tied the strength of the army not to the size of the aristocracy or the state’s ability to pay mercenaries, but primarily to the availability of a civilian populace for conscription, as well as an educated class to be assigned as officers. Naturally, with the shift towards total war came a shift in the conceptualization of warfare.

In this map of the eastern front during the initial stage of Operation Barbarossa, we see this shift. No longer is the focus on the movement of concentrated armies, but the shifting of front lines and the establishment of areas of control. As in the central thesis of John Keegan’s The Face of Battle, the conventional battle, as in the earlier periods, of two armies meeting each other on the field and confronting over the course of a few hours, at most a few days, and then moving onwards, is no longer relevant. Warfare in this stage consists of troop movements, offensives and defensive maneuvers, and sieges, and the goal has shifted in weight from tactical victory in battle to establishing strategic control over key industrial and population centers.

This model is functional in the case of conventional warfare, of two armies meeting each other in battle and establishing a rigid, impermeable front line. Currently, we can see this in the Ukraine war. Issue arises when attempting to use this model in visualizing asymmetric warfare, as in fourth generation warfare, the irregular party is able to permeate the lines of control with relative ease. Asymmetric warfare is not a warfare of front lines, but of gradient of control. The irregular actor isn’t limited to what is within reach of his army, as in the premodern and early modern case, or to the front lines of his theater, as in conventional modern warfare, but can act wherever there is some degree of operative capacity, wherever their cells, agents, and sympathizers exist and are able to act. And thus, as modern combat has moved the visualization from the one dimensional moving of a dot to the two dimensional shifting of lines, asymmetric warfare fundamentally shifts the visualization into a three dimensional shifting gradient.

Insurgency and asymmetric warfare is most effectively conceptualized and visualized as a probability distribution along along a two dimensional plane. It must be understood that in asymmetric warfare, the irregular party’s ability to permeate into areas of enemy control is fundamentally based on the fact that they are not a state apparatus. Where the shift towards total war and the visualization of warfare in front lines was due to the integration of the common people into the arms of the state and the growing importance of industrial production for the military effort, the shift towards asymmetric warfare and the visualization of war as a gradient along a continuous two dimensional plane is due to instances of popular rejection of state control. Fundamentally, the irregular party maneuvers at the level of the citizenry, whether through clandestine physical movement or through social means, such as recruitment, and momentarily reaches up into the local state administration by violent yet fleeting means, attempting to drive a wedge between the citizenry and the state as well as disrupting industrial production. The irregular agent doesn’t seek to replace enemy state control, just simply to disrupt it. And so this permeability requires the state not to think in front lines and black and white areas of control, but in a probability density gradient, where probability is dependent on regional influence of the irregular party.

The failure to visualize asymmetric conflict in this manner has led to great confusion, most recently in the war in Gaza today. Attempting to represent the Gazan offensive and the resulting confrontations in terms of front lines would be futile, as the Israeli political term “infiltration,” historically applied as a political tool to make any illegal crossing of the border seem far more insidious, is far more pertinent in this instance than some realize. Rather than taking Israeli territory into their own control, the Gazan fighters simply disrupted Israeli control of that territory in sporadic nature. There is no movement of the frontier lines, but simply varying levels and intensities of infiltration beyond them.

Leave a Reply